Reservoir Sampling

Algorithms Every Data Scientist Should Know: Reservoir Sampling

Here’s an example of this type of question that has been popular in Silicon Valley for a number of years:

Say you have a stream of items of large and unknown length that we can only iterate over once. Create an algorithm that randomly chooses an item from this stream such that each item is equally likely to be selected.

The first thing to do when you find yourself confronted with such a question is to stay calm. The data scientist who is interviewing you isn’t trying to trick you by asking you to do something that is impossible. In fact, this data scientist is desperate to hire you. She is buried under a pile of analysis requests, her ETL pipeline is broken, and her machine learning model is failing to converge. Her only hope is to hire smart people such as yourself to come in and help. She wants you to succeed.

The second thing to do is to think deeply about the question. This interview question probably originated in a real problem that this data scientist has encountered in her work. Therefore, a simple answer like, “I would put all of the items in a list and then select one at random once the stream ended,” would be a bad thing for you to say, because it would mean that you didn’t think deeply about what would happen if there were more items in the stream than would fit in memory (or even on disk!) on a single computer.

The third thing to do is to create a simple example problem that allows you to work through what should happen for several concrete instances of the problem. The vast majority of humans do a much better job of solving problems when they work with concrete examples instead of abstractions, so making the problem concrete can go a long way toward helping you find a solution.

A Primer on Reservoir Sampling

For this problem, the simplest concrete example would be a stream that only contained a single item. In this case, our algorithm should return this single element with probability 1. Now let’s try a slightly harder problem, a stream with exactly two elements. We know that we have to hold on to the first element we see from this stream, because we don’t know if we’re in the case that the stream only has one element. When the second element comes along, we know that we want to return one of the two elements, each with probability 1/2. So let’s generate a random number R between 0 and 1, and return the first element if R is less than 0.5 and return the second element if R is greater than 0.5.

Now let’s try to generalize this approach to a stream with three elements. After we’ve seen the second element in the stream, we’re now holding on to either the first element or the second element, each with probability 1/2. When the third element arrives, what should we do? Well, if we know that there are only three elements in the stream, we need to return this third element with probability 1/3, which means that we’ll return the other element we’re holding with probability 1 – 1/3 = 2/3. That means that the probability of returning each element in the stream is as follows:

- First Element: (1/2) * (2/3) = 1/3

- Second Element: (1/2) * (2/3) = 1/3

- Third Element: 1/3

By considering the stream of three elements, we see how to generalize this algorithm to any N: at every step N, keep the next element in the stream with probability 1/N. This means that we have an (N-1)/N probability of keeping the element we are currently holding on to, which means that we keep it with probability (1/(N-1)) * (N-1)/N = 1/N.

This general technique is called reservoir sampling, and it is useful in a number of applications that require us to analyze very large data sets.

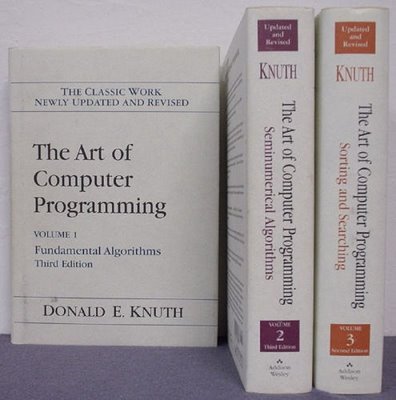

These Books Behind Me Don’t Just Make The Office Look Good

Interesting algorithms aren’t just for the engineers building distributed file systems and search engines, they can also come in handy when you’re working on large-scale data analysis and statistical modeling problems. I’ll try to write some additional posts on algorithms that are interesting as well as useful for data scientists to learn, but in the meantime, it never hurts to brush up on your Knuth.